“How would you like to see a real igloo?” Bryan asked.

“You bet!” I replied.

And that’s how I became caught up in a deadly Arctic blizzard.

A colleague and I met for coffee at a restaurant in Inuvik, NWT, a town in Canada’s high Arctic, when the ever-gregarious Bryan Samson joined us. He’d become famous by then. Many called him a ‘white Inuit’.

Bryan invited us to visit one of his close friends, an Inuit hunter, and the hunter’s family. The couple and their three children were part of a nomadic community. It moved along the coast of the western Arctic following the wildlife that provided them with food, clothing and meager incomes. Bryan said the community was just a few miles away.

“I’ve always wanted to see an igloo up close,” my colleague Eric said.

“Well, you’ll see a whole community of them,” Bryan said, chuckling. “It’s about an hour north of here by snowmobile.”

For Eric and I, making a quick trip to see a genuine igloo and to interview the family living in it was irresistible. Turns out, not even Bryan expected that in the process he’d be showing us how to build an emergency igloo at the height of a life-threatening blizzard.

We were in Inuvik on a news media junket. Our adventure that day was a side trip. A group of journalists had been flown from Yellowknife, NWT, to the small community perched in the middle of the massive MacKenzie River Delta. We were there to report on an announcement by some egocentric politician who wanted the dramatic setting.

With the lunchtime event over, fellow journalist Eric and I had adjourned to the town’s only restaurant. The others were in the town’s only bar. The plane scheduled to fly us back south to Yellowknife wasn’t due to leave until the next morning. Our news stories filed, we were killing time. And that’s when Bryan joined us.

“If we leave now, we could be back by suppertime,” Bryan said.

“Well, let’s do it then!” Eric replied.

Bryan was well qualified to be our guide. Few white men had the extraordinary skills needed to survive in the Arctic. Bryan did. He was 18 when hired by the fur-trading branch of The Hudson’s Bay Company. For the next 20 years, he worked in numerous tiny communities scattered along Canada’s 97,000 miles of Arctic coastline. He learned to live and hunt like the Inuit, and became fluent in numerous dialects of the Inuktitut (Inuit) language.

Bryan told us he’d hunted often with the men from the community. We’d also heard rumors that he’d fathered children in a number of Inuit families. Wife sharing was a common practice at the time. The Inuit culture was quite different from our own.

Eric and I were city dwellers. We’d arrived in Yellowknife a week earlier to report on a session of the NWT’s fledgling legislative government. We were ill equipped when the trip to Inuvik had come up at the last minute.

No worry, we both agreed. A quick side trip to see and photograph an igloo and back . . . what could go wrong? We assured each other we would be fine with our urban topcoats, gloves, wing-tip shoes and overshoes. Neither we, nor our employers, considered it necessary to invest in the knee-long hooded parkas, multi-layer wool and fir mittens, and sealskin mukluks everyone else was wearing. Big mistake!

We set off in the dark, even though it was early afternoon. In mid-winter there’s little daylight in the Arctic. What passes as daylight amounts to a few minutes of dawn just before noon followed immediately by a few minutes of dusk. Then it’s dark for the rest of the day.

I sat behind Bryan astride his snowmobile. Eric climbed onto the second snowmobile behind Bryan’s Inuit friend Qamut. The machines roared northward. At times we were dodging low brush on the snow-covered tundra, other times almost flying across the many smoothly frozen tributaries of the massive Mackenzie River Delta. It’s the Arctic equivalent of the huge Mississippi River Delta on the opposite coast of North America some 3,100 miles south.

A half hour into our trip, I glanced back. There was no sign of our companions. I tapped Bryan on the shoulder with an already frozen hand. Even lined leather gloves were no match for the 30 below F temperatures and wind chill from the speeding snowmobile.

Bryan pulled up.

He looked back, unconcerned.

“They’ll be along,” he said. “Give them a few minutes. Hop off if you like.”

I did. Bryan laughed as he pulled me back up onto the snowmobile.

“Asshole!” I said, trying not to smile. “Damn your miserable hide!”

I’d sunk in the powdery snow up to my thighs. The light snow had gone up my pant legs and down into my overshoes.

Bryan said something in Inuit, still chuckling. I didn’t understand.

“That’s the Inuit word for this kind of snow,” he explained. “The Inuit have 27 words for snow. Each word defines a particular kind or purpose.”

Our companions joined us 15 minutes later. They explained their snowmobile stalled just a few minutes after setting out. Qamut had deftly stripped the engine down, cleaned out snow plugging an air intake and had the machine running again in short order. There are no auto clubs in the high Arctic.

My watch said it was late afternoon when we arrived at the Inuit community. The trip had been much longer than Bryan estimated. We arrived almost an hour past the time we intended to be heading back. I secretly prayed that Bryan’s navigation skills were superior to his grasp of the passage of time.

Through the gloom we could make out large white mounds on the otherwise almost flat snow-covered landscape. They were igloos; a dozen or so. Faint glows were visible from vent holes at the top of them, evidence of the seal oil lamps that supplied both light and heat.

“C’mon,” Bryan cried as he leapt off his snowmobile. He dropped to his hands and knees on the hard-packed snow. Then he disappeared down a black hole. It was the entrance to a tunnel barely visible in the dark.

By now, Eric and I were so cold we could barely move. Our faces, eyebrows and hair were caked with snow and frost. We looked like actors in a winter scene out of Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Our hands and feet had the dexterity of frozen boards.

We crawled toward the opening where Bryan had disappeared. I went first, dropping about three feet in a flurry of snow. Eric dropped behind me. We were in a short narrow tunnel. We crawled about six feet toward a faint light and then up a vertical incline, entering a wonderfully warm single room – the inside of the igloo. The temperature probably hovered just above freezing, but to us it felt almost tropical.

“Over here,” Bryan said, barely visible in the light from two seal oil lamps. He introduced us to the man, a respected hunter, then to his kindly wife whose smile revealed a multitude of missing teeth, and to their three small children.

The youngest child, a baby, was snuggled in the hood of the indoor parka the mother wore. The eldest child, five or six years old, was making shy while fussing with a toy made of whalebone. He or she – not obvious because of the parka – was sitting on a wide shelf about two feet above the hard packed snow floor. The shelf was four feet wide and surrounded the inside perimeter of the igloo. It was the family’s living and sleeping area. The middle child, about two and naked from the waist down, was unmistakably a boy. Evidently he was not yet toilet trained. His excitement at seeing visitors initiated a yellow stream that arched away from him. It formed a pattern on the snow floor and promptly froze. The little boy was clad only in a shirt and tiny fur boots, but evidently was warm enough.

Later, I got a chance to whisper: “I checked, Eric. None of those kids looks anything like Bryan.”

Our host motioned the four of us to sit on the shelf. It was covered in caribou and seal hides piled two to three inches thick. The family joined us. Eric and I were curious about how their igloo was built and their lifestyle. We began asking questions. None of the family spoke English and only Bryan spoke Inuit. With Bryan translating and perhaps embellishing we suspected, the couple happily answered our questions in rich detail.

Suddenly a slab of something resembling a frozen steak appeared. Our hostess placed it on a flat piece of whalebone, produced a large knife and cut two-inch cubes from the foot-square slab. She gestured for us to help ourselves, then deftly lifted the baby from her parka hood and began to nurse it, oblivious to the strangers in her home. Bryan and Qamut eagerly popped the frozen cubes into their mouths, as did the two older children. It was seal blubber, a staple food among Inuit across the Arctic. Eric and I exchanged glances and popped a cube into our mouths. We had to work hard at not gagging as our host kept passing us more cubes. Refusal would have insulted their gracious hospitality. Let’s just say, frozen uncooked seal blubber has to be an acquired taste.

Before our hosts could insist on still more helpings of blubber, Eric and I whipped our cameras from the warmth next to our bodies and began taking pictures. The family happily posed for us. The light of the flashes ricocheted off the inner wall. I reached up and felt the glossy surface. Ice. Warmth from the igloo had melted the inner sides of the foot-thick building blocks and then froze, locking the blocks together and forming a solid barrier to drafts.

‘Brilliant,’ I thought.

“We’d better be on our way,” Bryan said finally. He seemed uneasy about something. The brief visit was over.

I thought: It’s going to be a very late supper, judging from how long it had taken us to get there. I hoped the hotel restaurant would still be open.

Moments later we were headed south toward Inuvik. That is, Eric and I assumed we were headed in that direction. A wild blizzard had roared to life while we were enjoying the hospitality of our hosts’ snug igloo. Visibility was a few feet at best – we were in a whiteout.

“Awe, we’re used to this,” Bryan shouted encouragingly over his shoulder.

I sure hope so, I thought, holding my mouth closed to keep the blowing snow out.

The longer we travelled, the heavier the snow, the stronger the wind and the colder the temperature became. Bryan finally stopped the snowmobile. I thought I’d never felt colder in my life. Eric surely had to be feeling the same. He and Qamut were back there somewhere.

Bang!

One second I was sitting on the back of Bryan’s snowmobile, the next I was draped backward over Qamut’s windshield and the front of his machine. In the driving snow, Qamut hadn’t seen us stop. He’d been concentrating on following the tracks of Brian’s snowmobile and had run into the back of it at about 20 miles an hour.

“This is going to get worse,” Bryan said, helping me up while shouting into my ear over the screaming Arctic wind. He ignored the accident after checking to ensure both machines were operational. “We’d better make camp.” The worried look on his face was not comforting.

Bryan hopped back on his snowmobile and went searching for any form of shelter. There’s not much in the high Arctic. He returned after a few minutes and led us to the leeward side of a small brush-covered hill. The unforgiving north wind was blowing clouds of snow over and around it, but at least it provided a bit of a windbreak.

Bryan got off his machine. The snow was hard packed under his mukluks. He pulled out a machete-like knife and plunged it into the snow. In seconds he’d cut loose a block of snow about 18 inches by 24 inches. He nodded at Qamut.

“We’re going to build a snow house . . . an iglusuugyuk . . . to wait out the storm,” he said. “Good snow here.”

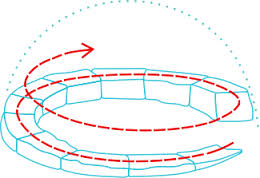

We learned an iglusuugyuk is an overnight snow house, a small temporary version of an igloo built much the same way. Blocks of snow for both are not rectangular, but like large bricks cut on an angle. Bryan and Qamut started with long narrow wedge-shaped blocks of hard snow, placing them in a large circle about 20 feet in diameter. The shape of the blocks created a spiral, around and around, leaning slightly toward the center and narrowing toward the top.

“You and Eric,” Bryan shouted over the wind. “Get in the center. You can help us put the blocks in place.”

We may have provided some legitimate help, but I’m convinced Bryan’s primary motive was to give us some shelter from the howling blizzard. Soon we were ready to place the last blocks. Bryan stood on a larger square block he’d cut earlier and placed in the center. I wondered about the purpose. Now, I knew.

He reached up and placed the final blocks, leaving a small vent at the top. The large block he’d stood on later would become our table. Next, despite being in the dark, we helped dig the entrance, first tunneling down sharply, then out horizontally five or six feet, and then up to the outside. The result was a surprisingly effective air lock.

Trying to be helpful, I began cutting small blocks and placed them on the upwind side of the tunnel entrance, to act as a windbreak. Eric came to help. Bryan stopped us.

“The snow will drift over the top of your windbreak and down into the entrance,” he shouted over the wind. “It’ll plug it.”

Sure enough, in just a few minutes drifting snow had begun to fill the entrance. We dug it out with our frozen hands. Eric and I removed the blocks and watched while the blowing snow passed right over the entrance. A little bit sifted down into the tunnel entrance, but not much. Lesson learned.

Back inside, Eric and I were surprised at how much warmer we felt out of the wind. Bryan and Qamut helped us smooth out the floor and then both went outside to move their snowmobiles into the shelter of the iglusuugyuk. They returned with arms full of goods from the storage hatches under the seats of their snowmobiles: sleeping bags, furs to sit on, a seal oil lamp with oil and wicks, matches, tin mugs and coffee, and of course a block of blubber. It tasted much better this time.

Qamut and Bryan chatted at length in Inuit while we ate and drank coffee heated over the seal oil lamp, luxuriating in the relative warmth. We could barely hear the wind through the foot-thick hard-packed blocks of insulating snow. But every so often, fine snow sifted down from cracks between the blocks above, reminding us of the raging gusts of wind outside swirling around our tiny shelter.

“We’ll sleep in these,” Bryan said, handing us sleeping bags. “The storm will blow itself out in a few hours.”

“When’s the next flight out of Inuvik for Yellowknife?” I asked. “Looks like we’re going to miss tomorrow’s flight.”

“Friday,” Bryan said.

This was Wednesday. Our editors wouldn’t be happy about paying for extra hotel rooms and meals. Eric and I hoped our feature stories and photos about the family and their igloo would soften their disapproval.

I was in a deep sleep when Bryan shook my shoulder. He assured me it was the next morning.

“Time to go,” he said, handing Eric and I each a few more cubes of frozen blubber. Frankly, I wasn’t eager to leave the warmth of the Arctic-grade sleeping bag he’d loaned me, much less leave the iglusuugyuk. We discovered later, Bryan and Qamut had slept in their parkas, struggling to keep warm in sleeping bags not designed for an Arctic deep freeze. The two men normally covered their snowmobiles with those dirty and ragged old sleeping bags to keep the snow off their machines.

We emerged to find the storm had blown itself out. But now, instead of swirling snow, all we could see in the darkness was a white expanse interrupted occasionally by snow banks or mounds, but otherwise absent of viable landmarks.

Somehow, Bryan and Qamut got us back to Inuvik, a testament to their consummate Arctic navigation skills. Turns out, the storm had grounded our flight overnight. It was scheduled to take off in a couple of hours.

#

“The Igloo” is Copyright 2015 By James Osborne. All Rights Reserved

#

Author’s Note: Although inspired by real characters, locations and situations, “The Igloo” is a work of fiction.

Photo Credits: Marcolm; freedigitalphotos.net,

Super story, As Always

LikeLike

What a wonderful work of fiction, James! An exciting story mixed with a bit of anxiety to entice the reader. Loved it! Thanks for sharing !

LikeLike

Loved it!!! Fabulous.

Marilyn

LikeLike

Great story! I didn’t know it was fiction until you said so in the end. I lived in AK for five years and this seemed pretty realistic to me. Good job!

LikeLike

Fiction? Really? Excellent story, James. I was so captured, I found myself wrapped in my blanket like a frozen cocoon. You may have written it as fiction, but it was live! Wow!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on J. Hale Turner, Author and commented:

Another jaw-dropping adventure with James Osborne. Warning! Warm parker, blanket and hot cocoa advised.

LikeLike

Fascinating work, Jim. I’m glad I wasn’t along, though I was raised in North Dakota and can relate to the cold. Double brrrrrrrrrr. Gayle

LikeLike

Great story!

LikeLike